No Human Foot Has Ever Touched Those Streets

Exploring Lovecraft's Poetry

Forests may fall, but not the dusk they shield.

H.P. Lovecraft, The Wood

Dear Readers, this is Deb. Before you read this piece by Michael, I wanted to thank him for contributing to My Unframed Life. I look forward to Michael’s work, knowing that he is a thorough, well read, faithful, down-to-earth artist and writer. As I read Michael’s latest piece, below, about poet H.P. Lovecraft, I pondered our world of great despair. It’s not an easy place to be without a spiritual anchor. I couldn’t help but think that the only conclusion to a hopeless world is hope. That a meaningless life can eventually be the upward spiral to redemption and purpose. Where we land spiritually is a calling we answer in a split second of clarity. Or not. Ironically, the little boy living inside of Lovecraft held onto life by writing about it as horrific (all we have to do is stare at a screen to be mortified). Lovecraft, to me, regarded beauty as undeserved, untouchable, yet in the pondering, this can lead to a deeper reflection of an extraordinary meaningful cosmos and a personal God as antidote to cosmic meaninglessness.

Thank you again Michael :) ox

Wishing you all a new year full of love and reverence in the small blessings. Thank you for supporting us here…

love, deb ox

I was twelve the first time I read The Dunwich Horror.1 I don’t remember every twist of the plot, but I remember the feeling clearly. A kind of wrong pull, the kind that flares up when you know something is going to hurt you and you move closer anyway. It bothered me. I got it almost physically, and still I couldn’t stop reading.

Back then, I didn’t know anything about H. P. Lovecraft. To me, he was just a name on a cover. But there was one thing I did understand, even without the words for it yet: fear. He and I shared that.

The Bond of Fear

I was a confused, anxious kid, scared of a lot of things I couldn’t explain and had no idea how they’d turn out. Lovecraft, in his own way, must have had the same struggles. That’s what created the bond as I read. It made me feel that the story in my hands, full of monsters, cults, and unspeakable horrors, came from something real. Whatever frightened Lovecraft was already inside me too: the adult world, sex, darkness, pain, loneliness. Sure, maybe the monsters he wrote about didn’t exist, but the terror did. That was real. Lovecraft knew it. And so did I.

“Then I perceived with horror that I was growing too old for pleasure. Ruthless Time had set its full claw upon me, and I was seventeen. Big boys do not play in toy houses and mock gardens, so I was obliged to turn over my world in sorrow to another and younger boy who dwelt across the lot from me. And since that time I have not delved in the earth or laid out paths and roads. There is too much wistful memory in such procedure, for the fleeting joy of childhood may never be recaptured. Adulthood is hell.”2

Isolation and Creativity

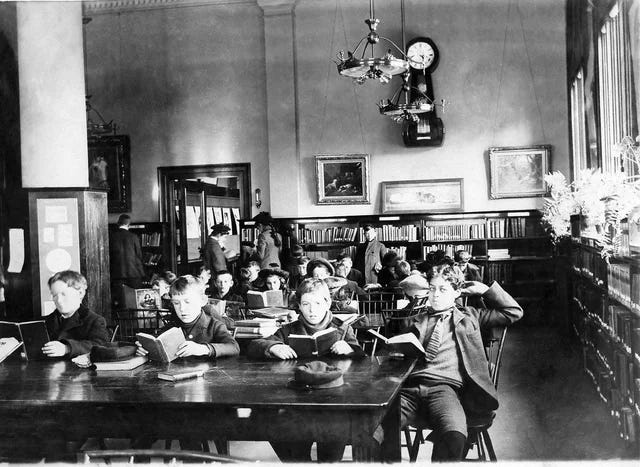

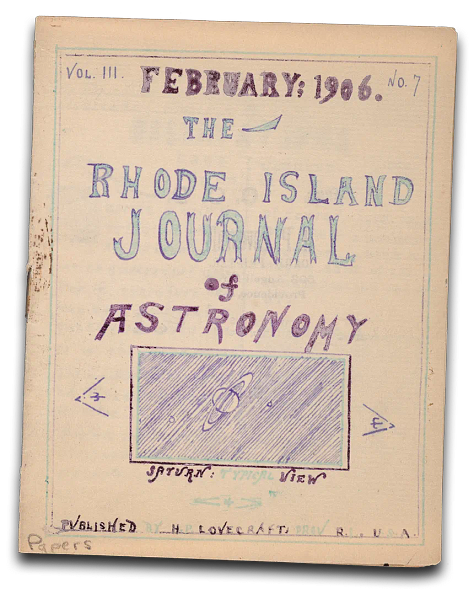

Lovecraft was a precocious child in a way that feels unsettling. He learned to read shortly after turning two, and by four, he was already writing stories and poems. Most people tell this as a story of early genius, but what it really makes me think of is his isolation. He was a kid forced to spend his time alone with books, in what we’d now call a dysfunctional family. His father was committed when Lovecraft was just three. His mother’s mind was deeply unstable, overprotective, and suffocating.

His childhood unfolded among books on astronomy, architecture, science, and metaphysics. As an adult, he scraped by correcting other people’s manuscripts, a job that carried no status and paid poorly. When he began writing more steadily, he mostly did it for friends. And when he tried to publish seriously, he often pulled back at the last minute. Accepting edits meant to make his work more palatable was impossible for him. Not out of arrogance, but because compromising with reality meant stepping into the world. And for Lovecraft, the real world was the problem.

The Protected Circle of Faith

For him, terror didn’t come from ghosts or demons. Horror came from the instability of the human mind itself. He was terrified of life. His horror was cosmic. Shaken by Einstein’s theory of relativity, the universe became, for him, a random arrangement of elementary particles:

“All is random, incidental, a fleeting illusion. There are no values anywhere in the infinite, and one thing is as true as another.”3

Relativity challenged traditional notions of space, time, and order. Combined with the influence of materialist philosophy, it helped shape Lovecraft’s view of the universe as indifferent and meaningless. Life, for him, had no meaning. But the anguish ran deeper than that. Even death had no meaning, because it offered no reconciliation. It didn’t save. It didn’t absolve. It didn’t release. It simply erased. He became a materialist, an atheist, yet one who never stopped remembering what it meant to believe. In a letter from the 1930s, he spoke of the “protected circle of faith” as something he had lost. And that loss, to my mind, emerges clearly in his poetry.

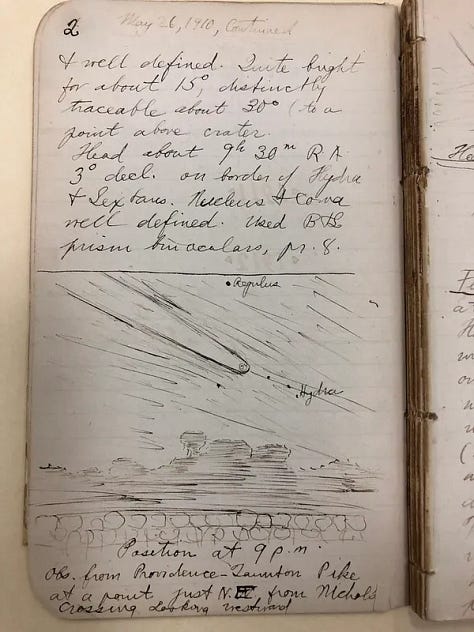

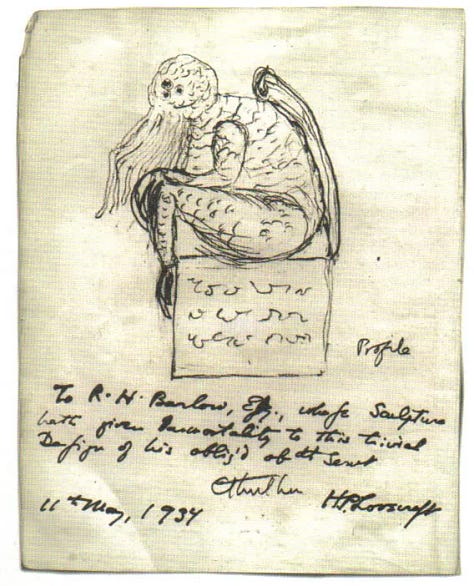

Fungi from Yuggoth

If Lovecraft’s stories are carefully built machines, his poems feel more like cracks, or fissures into his mind. They’re scattered, not neatly arranged or catalogued, but some are collected in Fungi from Yuggoth, a sequence of thirty-six sonnets.4 They are difficult, disorienting poems, built on strange connections between words and ideas. Reading them feels like stepping into another dimension: parallel worlds, secret doctrines, fragments of memory and knowledge all twisting together. There’s a kind of poetic ecstasy in it, the thrill that comes from glimpsing truths you’re not supposed to see.

Read Star-Winds. It’s a poem about twilight, about autumn, about that precise hour when everything feels like it’s on the verge of remembering something. The wind rolls down the hills, dead leaves twist along the streets, chimney smoke moves in ways that don’t belong to this world. The lit houses are little shelters, small circles of warmth. But the star-wind carries dreams, and it carries away far more than it gives. It’s a cosmic vision, sure, but it’s also deeply domestic. It’s that ache of standing outside and looking in.

XIV. Star-Winds

It is a certain hour of twilight glooms,

Mostly in autumn, when the star-wind pours

Down hilltop streets, deserted out-of-doors,

But shewing early lamplight from snug rooms.

The dead leaves rush in strange, fantastic twists,

And chimney-smoke whirls round with alien grace,

Heeding geometries of outer space,

While Fomalhaut peers in through southward mists.

This is the hour when moonstruck poets know

What fungi sprout in Yuggoth, and what scents

And tints of flowers fill Nithon’s continents,

Such as in no poor earthly garden blow.

Yet for each dream these winds to us convey,

A dozen more of ours they sweep away!

Take The Lamp, for example. There’s an ancient lamp, hidden in a place no priest could interpret, holding oil that is sacred… or maybe cursed. When it’s lit, it doesn’t reveal comforting truths. It gives visions that leave a mark, that scar the mind. Knowledge illuminates, but it doesn’t save. It burns. It’s a reversed theology.

Outside the circle of faith, no revelation brings peace.

VI. The Lamp

We found the lamp inside those hollow cliffs

Whose chiseled sign no priest in Thebes could read,

And from whose caverns frightened hieroglyphs

Warned every creature of earth’s breed.

No more was there—just that one brazen bowl

With traces of a curious oil within;

Fretted with some obscurely patterned scroll,

And symbols hinting vaguely of strange sin.

Little the fears of forty centuries meant

To us as we bore off our slender spoil,

And when we scanned it in our darkened tent

We struck a match to test the ancient oil.

It blazed—great God! . . . But the vast shapes we saw

In that mad flash have seared our lives with awe.

And then there is Hesperia. Here, Lovecraft almost stops talking about horror. He speaks instead of a land that exists only in memory, or in longing. A place where every kind of beauty has meaning, where time begins as a luminous river. It’s an Eden, but one we can never reach. Dreams carry us close, he says, but no human foot has ever touched those streets.

XIII. Hesperia

The winter sunset, flaming beyond spires

And chimneys half-detached from this dull sphere,

Opens great gates to some forgotten year

Of elder splendours and divine desires.

Expectant wonders burn in those rich fires,

Adventure-fraught, and not untinged with fear;

A row of sphinxes where the way leads clear

Toward walls and turrets quivering to far lyres.

It is the land where beauty’s meaning flowers;

Where every unplaced memory has a source;

Where the great river Time begins its course

Down the vast void in starlit streams of hours.

Dreams bring us close—but ancient lore repeats

That human tread has never soiled these streets.

So the man who built one of the most merciless cosmologies in modern literature carried deep regrets and countless nightmares that haunted him from childhood. Despised by his own mother, who called him “hideous,” he must have absorbed that judgment early on. She told him about horrible creatures following her in the street, ready to seize and tear her apart. She spoke of dreams that tormented her, of a nameless pain that consumed her.

Maybe that’s the picture, in the end: a woman in pieces, and a son trying to put those pieces back together through stories, trying to give shape to the fear and pain he lived with night after night in his childhood bedroom. Near the end of his life, short as it was, he found a strange kind of balance in illness. He had feared dying insane and institutionalized, like his father. Instead, he was dying of cancer. And that, strangely enough, was a consolation.

Many thanks to Deborah T. Hewitt for this space, and to you for taking the time to read.

Michael

First published in 1929, it tells the tale of the monstrous Wilbur Whateley and the strange events surrounding his family in the rural town of Dunwich, Massachusetts. The story combines elements of cosmic horror, folklore, and the supernatural, illustrating Lovecraft’s themes of fear, the unknown, and humanity’s smallness in the universe.

H.P. Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life by Michel Houellebecq, pp 30-31.

From a letter of the 1920s.

Fungi from Yuggoth was written by H. P. Lovecraft in the 1920s. The poems explore cosmic and otherworldly themes, blending elements of fantasy, horror, and philosophical reflection. Unlike his prose, which often constructs elaborate narratives, these sonnets are fragmentary and lyrical, creating “fissures” into Lovecraft’s imagination and offering glimpses of memory, dream, and forbidden knowledge.